IN Conversation with Dr. Christopher Perrin

Monday, December 5, 2022

Dear Hill Country Families,

Recently, we were honored to have Dr. Christopher Perrin join us virtually for professional development with our faculty and staff. Dr. Perrin is a national leader, author, and speaker for the renewal of classical education and the co-founder and CEO/publisher of Classical Academic Press. He hosts The Christopher Perrin Show, in which he discusses topics related to renewing and advancing classical education. He also serves as the President of the Alcuin Fellowship, which has brought together educators from around the nation passionately committed to the renewal of classical education.

Enjoy this month’s [IN] Conversation—edited for brevity and clarity—with Dr. Christopher Perrin below.

Dr. Christopher Perrin:

When was the last time you were so caught up or transfixed in conversation that the world disappeared? Have you had some times recently when you’ve had a conversation with others, perhaps coupled with food or drink, where you lost consciousness of the daily trappings that were about you?

The word symposium, in Greek, means “with drinks” and conveys an undistracted time with friends to converse and study the things that are most worthwhile. The Greek word scholé, “leisure,” is at the root of the English word “school,” and, alongside symposium, conveys this idea of contemplation and restful learning. But that’s not often what we think of when we think of school, is it? There’s not a lot of scholé in American progressive schools. From scholé we also get the German word schule, the Italian scuola, the Spanish escuela, the French école, and the Latin schola. While contemplation and restful learning are at the foundation of the idea of school, the trouble is that we’ve inherited patterns of doing school that are quite opposite to contemplation and restful learning. We’ve been so formed by these patterns that we’re not even aware of them. But what if school was informed not just by what we’ve inherited, but by this idea of scholé, this tradition of contemplation and restful learning?

For those who want to study the origin of this word scholé, look at Aristotle’s Politics, Books 7-8, where he discusses scholé. For Aristotle, scholé was one of the highest human activities, so that we could engage in theoria, often translated as “contemplation.”

There’s a story in Luke 10 that is worth considering related to this idea.

“Now as they went on their way, Jesus entered a village. And a woman named Martha welcomed him into her house. And she had a sister called Mary, who sat at the Lord’s feet and listened to his teaching. But Martha was distracted with much serving. And she went up to him and said, Lord, do you not care that my sister has left me to serve alone? Tell her then to help me. But the Lord answered her, Martha, Martha, you are anxious and troubled about many things, but one thing is necessary. Mary has chosen the good portion, which will not be taken away from her” (Luke 10:38-42).

Are we providing an education to our children that is more, based on this scene, like Martha or Mary? Martha was distracted, anxious, and troubled about many things. Mary had chosen the good portion, sitting, or resting, at the Lord’s feet and contemplating his teaching.

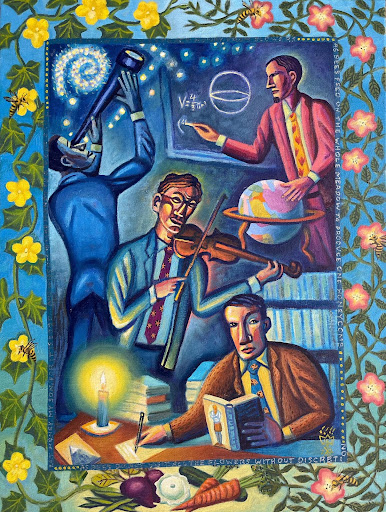

There’s a painting, one you haven’t seen before because it is brand new, worth considering related to this idea.

This painting shows Daniel and his three friends—Shadrach, Mischach, and Abednego—who were gifted by God to study and understand all the wisdom and literature of the Babylonians. They were ten times wiser than all the magicians and wise men in the king’s court. During a time of exile, these four men were gifted and knew how to, with discretion, study literature outside of the covenant of Israel.

You also see several quotes in the painting about bees and honey. Bees spread pollen but make honey. They do not go to every flower. St. Basil the Great writes about this and says that when it comes to being a student, we should be like the bee. The bee does not go to any flower without discretion; it goes to some and leaves some behind. We, too, should have discretion like the bee, passing over certain kinds of literature and taking others in. There is a sense in which Hill County is like a bee hive, with teachers and students going from flower to flower and making something sweet. We need to have the discretion to know what flowers to take from and which ones to leave behind.

I have two points for you to contemplate this morning:

- We become what we behold. We become like that upon which we gaze. So whether it’s TikTok or endless reruns of The Office, we start to become like these things. What are we regularly beholding?

- We study what we love. We can’t love something if we don’t linger over it and savor it. You can’t “cover” material and expect students to love learning. Covering material isn’t even learning, even if students can spit it out on a test on Friday and get an “A.”

C.S. Lewis says we should teach far fewer subjects and teach them far better. I think this is a challenge for all of us because we’ve inherited a system of teaching that focuses on the opposite. If you want to look at an educational model different from the progressive liturgies we’ve inherited, look at the Christian monasteries. Look at monastic education, which provided the dominant form of education in the West for about 1,000 years, from about 500 to 1400 AD. The monastic blend of praying and working in harmony among brothers can inform how we think of a neo-monastic embodiment that would challenge what we’ve inherited in progressive liturgies and models.

As we try to recover an approach to education that cultivates wisdom and virtue, we need to look back to models that have done really good work. Like the bee, we need discretion with what to take and what to leave. We’re not going back to wax tablets, for example, but we will look at the ideas and practices that created environments where scholé led to contemplation and resulted in wisdom and virtue. Virtue means excellence, human capacity fully developed. Virtue is man coming into his own with strength. Virtue isn’t necessarily taught but caught, and it begins with imitation.

But cultivating virtue in students takes time, and we need to make time and room for contemplation. Wherever we find something good, true, and beautiful, embodied in art, literature, or people, we should gaze, and gaze, and gaze, and linger, and talk, and have tea, and coffee, and discussions. We shouldn’t hurry on to the next thing. We should be careful not to fall into the trap that Martha fell into of being distracted, anxious, and troubled about many things. We need to follow the example of Martha’s sister, Mary. So let me ask you: do you set aside time where there is that kind of engagement, that kind of possibility for ongoing contemplative reflection and conversation on the things that are most worthwhile?

I’ll close with this—we can’t become imbalanced and just sit and look at art all day. Some of you teachers are thinking, “I have content to teach!” Well, let’s think of it like the Sabbath: six days to work and one day to rest. Six and one. What if we could learn to prepare contemplative exercises and discussions with this ratio in mind in order to model this approach to learning, to living, and create better liturgies for students in our schools?

In Him,

Matt Donnowitz, Head of School